A review course will provide the material you need to learn to pass the CPA exam. Sometimes if something is handed to you, you take it for granted or find fault in it. When you think that a subject is not being taught clearly, or is boring, go find a better source to learn about the subject. Pull out an old text book or search the internet for a better explanation or for examples. One of two things will then happen: 1) either you will get a better understanding or 2) you will realize that the explanation provided by your own course is more helpful than other sources. But more importantly, you will realize that you are your own teacher, not your review course, and it is your responsibility, not the review course’s responsibility to teach yourself. Be grateful for the resources provided by your review course, as you are your own teacher and they are helping you.

Be grateful for the internet. If you don’t understand a practice question, type it word for word into a search browser. The practice questions that your review course provides are from the CPA exam test bank. No matter what review course students are taking, they all most likely are practicing with the same questions. Many other students have stumbled over certain questions, and, unsatisfied with the answers provided by their CPA review course, have posted a plea for help on understanding the question to the world wide web. And thank goodness there are those who like to post answers. There are free resources like Khan Academy that will teach topics in detail, such as economics, stock derivatives, present value calculations.

Look at each answer as you go along when you take a practice test. This can go against the grain for some people who don’t think they will be able to assess themselves if they cheat by looking every few minutes, or who are too proud to need to look at the explanation. It is no more cheating than answering a professor’s question in class and getting immediate response as to whether you are right or wrong, and why. You will learn more from the answers you get wrong than from the answers you get right. You can learn a lot by getting immediate feedback on your wrong answers, and get them out of your system before exam day. Your goal on exam day is total confidence about your answers.

Be interested in what you are learning. If you have been lucky enough to have been close in your life to people who were bona fide geniuses, you may have noticed that they had an interest in things they studied. Sure, exterior motivation can make grades a game, competition can make a person exert more effort, fear can prevent someone from not doing their work, and inspiration from a good teacher can make things interesting, parental guilt can make one behave, but these are all exteriorly imposed interests. While genius comes in all forms and personality from humble to braggart, from well-intentioned to twisted, from quiet to loud, genius does have in common an element of interest in what is being studied. If you have not ever had geniuses in your life, then look around you at people you know that have certain traits or strengths. Even if these people aren’t all-around geniuses, think about those traits they are good at. Indeed, especially since those people are not geniuses, for them to be good at certain things required them to be interested in those things.

So while many people will tell you to motivate yourself by envisioning yourself with the three letters CPA on a placard or a certificate on your wall, or the envy of your friends, or sticking it to your boss or escaping your life of drudgery or pleasing your family, realize these things are exteriorly imposed interests. Realize these things will motivate you but they won’t help you understand what you are studying until you actually can find something about the materials that is interesting. One of the best ways to get interested in the materials is to practice the Task Based Simulations. The biggest benefit of practicing the TBS sections of the homework is not necessarily “to prepare you for the TBS section of the exam.” Instead the biggest benefit is to 1) give you a vision and example and allow you to imagine how the information is used in real life which in turn will 2) interest you in the subject and your interest will in turn 3) allow you to learn the subject in a deep way.

The math on the CPA exam is about 4th grade level – almost all the percentages are 10%, almost all the numbers are an even million. The calculator isn’t necessary, it is just there for security and a sense of order and as a record of the numbers and operation that you have performed, so you can check your work. In most problems you can do the math in your head faster than the time it takes to type it into the calculator.

Be aware that accounting is about imagination, not math. This is the key to getting interested in the subject or the problem. You look at numbers and you see in your mind’s eye a warehouse, with shelves loaded with boxes of inventory, and a loading dock and a grisly old warehouse manager with crumpled, coffee stained receiving reports piled up on his desk. You look at numbers and you see a drafty, echoing manufacturing plant, with crowded store-rooms of raw materials, and stations in various stages of unassembled parts, welders, metal dust, noise, forklifts, the time card clock, benches of technicians. You look at an org chart and you see glass offices with long desks and executives behind a monitor, a phone, memorabilia, post-its, white-boards, file folders, books, a visitor’s chair; you see the executive getting up, roaming the halls, rubbing elbows, bringing blue-prints or plans or reports to other executive’s offices.

It is sometimes hard to get a picture of what is happening when you see a practice question that starts in the usual sterile way: Hall, CPA is engaged to blah blah blah. All your mind’s eye may be envisioning is a cold, empty walled (ok fine, maybe there is a portrait of the firm’s ancient founder) accounting office with unfriendly clients, uncomfortably formal clothes and no joking allowed. But why can’t Hall, CPA be an accounting office with 70’s art and a throw rug with a receptionist who decorates the reception area with crystal balls and beads and an alcoholic boss and the clients are crying wives and young entrepreneurs. Why not? Not that you would want to work there, but it is a more interesting question that way.

If you find yourself looking at a concept that you have to learn and recoiling with the thought “I will never use this knowledge in my life, I am just going to close my eyes, hold my nose and swallow it and then regurgitate it on the exam” you are missing out on interest. If studying auditing is boring to you, watch some tv crime shows where you see the FBI interrogate suspects, find clues, uncover plots. If studying BEC is boring, find some purchases you may want to buy, compare them as to their useful life and the value they will provide versus their opportunity cost. If studying REG is boring, get into a contract with someone and find out how important it is to know the law when the person turns out to be a crook. You are only limited by your imagination when dreaming up “will this knowledge ever be useful or entertaining to me.”

Do not think that what you learned in college will get you through the exam without a review course. What you learned in college may be obsolete by the time of the exam. Just because you had to do a whole research project in school on what is considered an extraordinary event doesn’t mean that the rules can’t change by the time you get out of school, and suddenly the whole concept of extraordinary events that you learned in college has been trash-binned. Do not think that what you learned in the workplace will get you through the exam. What you learned in the workplace may be, or probably is, different than the ideals the exam tries to test. Just because your accounting office allows a self-employed person to have losses year after year, and successfully defends those losses in IRS audits, doesn’t mean the exam won’t expect you to treat such activities as hobbies. Do not think that the review course infallible, especially the lectures. Sometimes the lecturer will mis-speak without realizing it, you need to be able to question concepts that do not make sense, use the internet and see if the concept can be clarified, and not be angry with a course that allows materials to be presented imperfectly. It is up to you to learn what you need to learn, whether your sources are correct or not. When in doubt, you can always read the authoritative literature, access to which is provided free to CPA exam candidates. You will find that your review course has actually done a very good job of presenting what you find to be written in Greek in the authoritative literature.

Design your own teaching tools and lesson plans. You know yourself best, make your activities something that you know you will learn from, not something that will put you to sleep. It may be as simplistic as reading a chapter and doing 30 multiple choice questions a day. Or it may involve note-taking, flash-cards, listening to videos. At one point I got frustrated with the randomness of the questions of my computerized review course. I wanted to be able to flag certain questions in a more efficient manner, and be able to be asked certain questions over and over that I felt to be good at teaching a concept, and I wanted to avoid other questions that I felt were a waste of time because they were too easy and too time-consuming. I wasn’t satisfied with the flagging ability of the software, which I found too clumsy. So I started to painstakingly copy and catalog each question into a word document. It was an extremely laborious task, but the end result was that I had access to all the questions, organized and flagged with the symbols I could use to locate and ask myself the questions that I found the greatest teaching questions.

Even though everyone learns differently, I believe that certain actions are indispensable, and that quite possibly if you do not do these actions you will not pass:

- Take notes and/or create your own flash-cards. I prefer flash cards because they force you to distill the essence of a concept and are easier to review later as refresher. Writing notes serves the important function of forcing you to pay attention to what you are studying – you find that sections you glossed over or day-dreamed through suddenly make sense and come into focus.

- Do the practice questions

- If your text book is more than a year old, check that the information is not obsolete or superseded. Sometimes the lectures online will have information that contradicts the text book you are studying – and the reason may be that the lectures are up-to-date but your text book is old. Ask your review course to send you any errata or text-book updates. (Sometimes of course, the lectures simply have a lecturer who mistakenly says the wrong thing, so the text may be right). The point is to be very careful if the text is even one year old. Accounting standards are constantly converging, being re-organized, clarified, changed.

When watching a video or reading about a concept, if you find yourself not paying attention, do not go further. Re-wind or re-read. Most likely you will again wander off. Stop and re-wind as many times as is required for you to pinpoint what you have been glossing over. After you have pinpointed what it is, learn it. If you really cannot learn it, then make a note to yourself to come back to it later, after you have gained a wider foundation by learning the rest of the course. Do not discount the value of learning anything, or make the decision not to learn it. Note the area. Take the time to understand it or make the effort to come back to it later.

If your videos provide the ability to speed up or slow-down the video, play with the speed. If you have heard the lecture many times, reviewing it at double speed will help you review without boring you.

Learn the basics before getting into the details. This often requires a spiral approach, going through the entire course and all the materials and then starting at the beginning again to fill in the gaps or the things that you may not have grasped fully the first time around, or that you forgot.

Use practice questions as a learning process, not as a critique. Areas that were hazy when you were reading or listening to them will begin to make sense as you do the practice problems. Don’t be worried if you get most of the problems incorrect your first couple times through them. Your score on the practice problems when you are first learning the material has absolutely no correlation with what your score will be after you understand and start to master the material.

Take seriously the amount of time it takes to learn the materials. It takes several hundred hours. When you hear someone tell you that all they did was lock themselves in a room and study intensely for one weekend and passed, understand that the truth may be a bit different. What probably was the case was that they were carelessly reading the material for months and weeks, watching tv, taking days away from the materials, not taking their studies seriously, when all of a sudden the seriousness of their situation (as in, their scheduled day for the test) forced them to focus intensely. There is nothing like the enormity of the deadline to force a person to focus. And it is true, a weekend of focus will get you through the exam. However, realize that IF the person passed it is BECAUSE the person DID look at the materials for weeks and months before that “one weekend of studying.” Those months and weeks of careless reading or thumbing through the materials were actually laying the foundation and allowing the person to mull over concepts, get used to terminology, get familiar with the subject. There is no way to pick up the materials for the first time and focus in one weekend. Do not believe it. Do not try to do it. That is the reason the majority of candidates fail. It is expensive, it is a lie that it can be done that way, it is a brag that you will regret believing, don’t believe it.

Be willing to change your approach, study style, and type of skill for each section. While concepts overlap, treatment of those concepts differ, so do not get stuck in a rote expectation of how to answer a question. In FAR you may be asked to calculate or present a derivative, in BEC you may be asked to write an explanation about how derivatives work, in audit you may be asked to look at the risk factors of derivatives. So don’t blow off studying a topic because you think you know everything about it from a different section, or because you think it will only be tested in a certain section. Have the humility to look at it again.

The research database for FAR has only be one set of standards to search through (FASB). However, AUD has a whole array: at, ar, ar-c, et, bl, cs, qc, pr, pfp, cpe, pcaob, ts, vs, au-c. So while just being able to use search skills may carry you through FAR, AUD requires you also know which database is which. Don’t assume just because you were proficient with a concept or task when taking section of the test that you won’t have to study or practice it in a different way when you take a different section.

Another thing different about the research in AUD versus the other sections is that the AICPA clarity standards organize each standard with the following sections:

Intro

Objectives

Definitions

Requirements

Application

The standards go on for many pages, so it is easy to lose your orientation as to which section you are in. One hint is that the paragraphs in the application section begin with the letter A.

Look at the research questions carefully to see which section your answer will be in. Though you may see the same words in each section, you will need to pick the right section based on whether the question is asking for the “definition” or the “auditor’s objective” or “auditor’s procedure.” Also, many paragraphs have what looks like the answer in a short preface, but the subsequent paragraphs give the details that the question looks for. For example, if the question asks for “auditor’s responsibility for fraud” you may search and find a paragraph titled “Responsibility for fraud.” It may be tempting to choose that paragraph. However, upon closer inspection, the next paragraph is the subsection “Management’s responsibility” and then the paragraph after that is “Auditor’s responsibility.” It is the third paragraph that is the answer to the question.

In the testing center itself

My own experience with the testing center has so far been very enjoyable. There is a comfortable chair, ample size monitor, mediocre keyboard but at least with number pad, and noise-cancelling headphones. Compared with my own study area at home, on a tiny laptop sitting on a couch or my bed, and millions of interruptions, kids, mess and other people watching tv, etc, the testing area is far more conducive to “getting in the zone.” If you have been well-prepared you may feel a bit of a high and a sense of effortlessness while taking the exam.

Be sure to go onto the AICPA website and take the test simulation. Even though your review course has its own simulation, you should still go onto the AICPA website and use theirs at least once. They have a tutorial that teaches you how to split a screen in half while doing task-based simulations, how to input formulas into their mini spreadsheet answer spaces, etc. The search mechanism in the research questions is different, the calculator is different than in the review course simulations. My first test I took I did not know that I should have tried out the AICPA website and I was disoriented at first by the differences. I was pleasantly surprised by the calculator which was much better than the one I had practiced with during my review course.

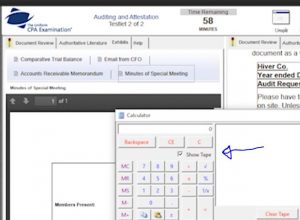

Note that the calculator has a check mark that says show tape:

You always want this box checked – be sure not to accidentally uncheck it, or you will miss out on a great tool.

There is also a button that says “Clear Tape” which I recommend that you never touch. Leave the tape alone for the entirety of the test. There are so few calculations that require the calculator that by leaving the tape as a running record, problem after problem, you have a record of your thought process for those few questions that you used it for. This is useful come to back to when you are reviewing your answers before submitting each testlet.

You are provided with two dry-erase laminated graph paper scrap sheets. If you fill up one you can raise your hand and request to replace it with an empty sheet. Be sure to raise your hand ahead of time as you anticipate needing the sheet, since it may take a minute before the test administrator notices you and comes to you. Some people recommend reserving one sheet throughout the test that you have jotted your last minute notes, memory aids, etc on before the test started (there is about 7 minutes of semi-free time that each candidate is allowed before the exam begins – the candidate supposedly is supposed to be spending those 7 minutes reading the contract and rules on the computer, however there is nothing against the rules with using those 7 minutes to write down all the lists, formulas, concepts that you are afraid you may blank out on before you begin the exam.) Many times the two sheets of paper are sufficient for the entirety of the exam (one side for each testlet, max of 4 testlets). I personally write as small and neatly as possible, and number each problem in order to be able to come back to my calculations. However, I have found that I rarely flag a problem to come back to that involves calculations. Usually the only problems that I flag are concepts with no calculations. So even though I have set up each sheet neatly in case I want to revisit, I never actually revisit them. The process of being neat and orderly still has a calming and focusing power.

Be sure to not spend too much time on any one testlet. My first exam (FAR) I went very slowly and methodically through the first 3 testlets because I incorrectly estimated the amount of time I would need on the fourth testlet. I assumed that because there was 4 hours for 4 testlets that each testlet would be on target if done an hour each. I went very slowly, double checking each question several times. I had an hour and fifteen minutes available for the fourth testlet, which I felt was well ahead of target, however I couldn’t have been more deluded. The fourth testlet is composed of 7 task-based simulations which take about 15 minutes each. Being that I hadn’t practiced the format, the first one took some time to get the hang of what they were asking for. The second one as well. After I did the third one, with 30 minutes left, I assessed my progress and realized my mistake in time estimation. By then I really had to go to the bathroom badly, my heart began pounding, and I went into full panic mode, doing the next 4 problems in 5 minutes each. I went back to check over my work, starting at task based simulation number 1, and spending a minute reviewing (and correcting) each one, and when I got to review the last problem I suddenly went blank on the formula (granted I had “known” the formula blindly a few minutes before) but suddenly I started second guessing myself, and started changing all the formulas. Then I triple guessed myself, then quadruple guessed myself, my blood pounding so hard to my brain I don’t know what I was thinking, wildly typing in numbers and having them cascade into each other like dominos, changing them over and over with each realization that there was another element that I needed to change. Finally I changed my last 5 numbers in a row with 5 seconds, 4 seconds, 3 seconds, zero seconds, submitted the damn test and realized that I had changed perfectly good answers for no reason, just because I was in panic mode.

So don’t do that.

One last piece of advice. Don’t listen to anyone who says you are studying too hard and that it is a waste of time to shoot for a high score, since the passing requirement is only 75 percent. Instead, approach the exam like an engineer building a bridge. Over-engineer it, for safety. Shoot for a high score. The exam is extremely expensive. With four children to support, every hour of study was an hour less of overtime wages, which was a huge blow to my income. I could not afford to fail any section of the exam (could neither afford the cost nor the afford the time to re-study), and so I studied with the goal to get 90 percent on each section, for the margin of safety. I knew there was a high chance I would freeze up on the exam, a high chance I would make stupid mistakes under stress. I wanted the luxury of at least understanding the subject so thoroughly that I would be able to survive being side-swiped by such things.

AUD Score: 97 – Attended: 11/02/2016 12:41:00

BEC Score: 89 – Attended: 07/07/2016 09:08:00

FAR Score: 90 – Attended: 06/08/2016 12:58:00

REG Score: 91 – Attended: 08/11/2016 13:30:00

Thank Nitza. I really enjoyed this article. I especially enjoyed the paragraph explaining how accounting is more about imagination than math. Math was not my strongest subject in school so I often wonder if I have what it takes to be a good accountant. The section you wrote about taking the CPA exam was very insightful and packed with great info to help one prepare for the test.

Thank you! Tara