TIME TO DIG IN!

The next step, after entering your bank account transactions, is to output some basic reports, to see the effect of your entries.

If you are working in excel, the closest thing you will get to a report is a pivot table. However, you will need to have a structure in mind to guide your creation of the pivot table. If you are not familiar with the concepts behind basic financial reports and how they are supposed to be presented, I recommend that you do not use excel. Instead, use a bookkeeping software that creates the structure for the basic recommended reports.

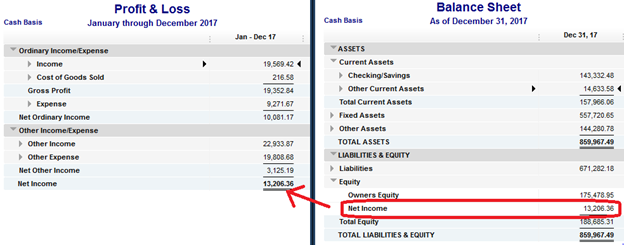

Here are the two most basic financial reports:

- The Profit and Loss. This report may be referred to using various names. For our purposes, consider the following to be synonyms: “Profit and Loss Statement,” “Income statement,” “Statement of Revenues and Expenses,” “Statement of Operations.”

- The Balance Sheet. Again, known by various names, any of which are sufficient for our purposes: “Balance Sheet,” “Statement of Financial Position,” “Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Assets.”

The Profit and Loss is the report that is most familiar to people.

However, an accountant will usually spend their initial time looking at and fixing the Balance Sheet, not the Profit and Loss. The reason for this is that the Balance Sheet is a major way to proof the Profit and Loss.

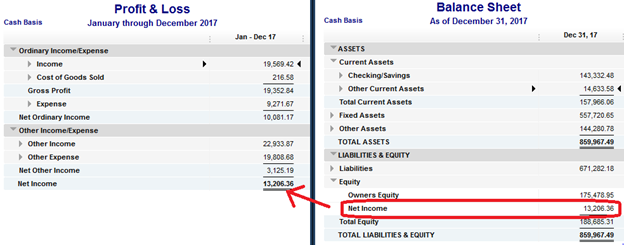

The Balance Sheet has, as one of its components, the net income. If your software program allows you to drill in on the line item “Net Income” on the balance sheet, you are in essence creating the Profit & Loss report.

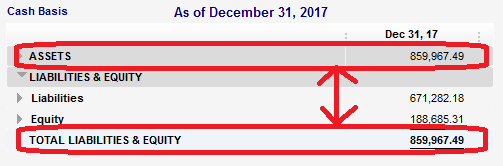

Because a Balance Sheet has to, well, balance, a change in the balance of any one account (a bank balance, a loan balance, or owner’s equity) will affect the balances of the remaining accounts.

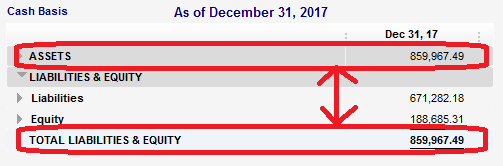

The Balance Sheet represents “The Basic Accounting Formula.”

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

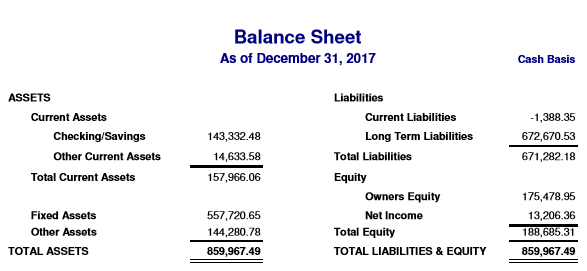

Sometimes a Balance Sheet is presented in a side by side manner, to emulate the formula, and to emphasize that debits (which represent increases to asset accounts) are on the left and that credits (which represent increases to liability or equity accounts) are on the right.

(left side) Assets = (right side) Liabilities + Equity:

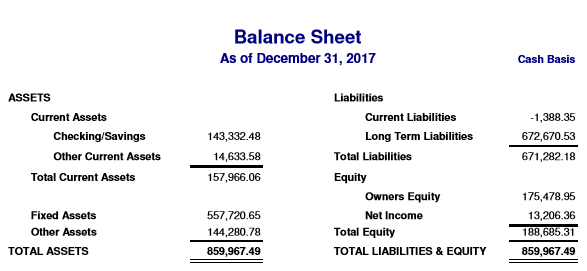

Note in the example Balance Sheet given above, that there is a negative number in one of the accounts (Current Liabilities). This is where an accountant usually frowns.

A negative number is contrary to what is expected. Sure, it is possible for a liability to be negative (for example, by overpaying a credit card), however, it is more likely that the balance is just plain wrong (why would anyone deliberately overpay a credit card?).

It is for this reason that an accountant usually asks the client for their year-end bank statements, loan statements, credit card statements, year-end inventory count, list of equipment on hand, etc. The accountant then looks at these items and compares them with the Balance Sheet.

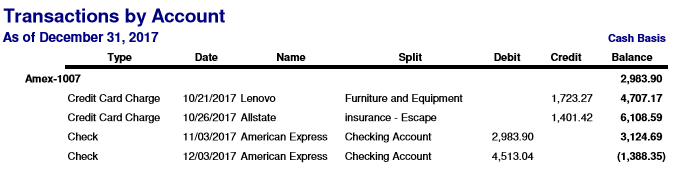

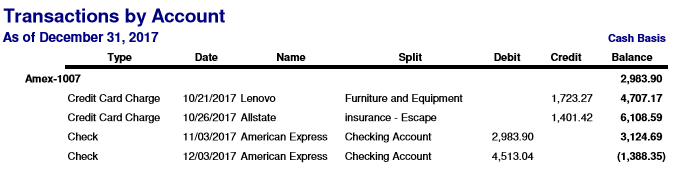

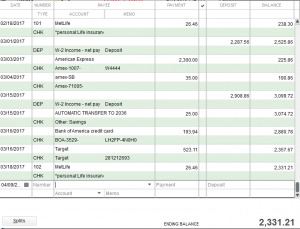

Does the credit card company really agree that they owe you a refund for the overpayment? Or did you just forget to record some of your credit card purchases? Drilling in on the line item may uncover something like this:

Which shows that no credit card charges were entered after October 26, 2017. Were there really no credit card purchases after that date? Very unlikely, considering that a payment dated December 3rd indicates there was probably a running balance of at least $4,513.04 in mid-November. More likely the bookkeeper went on holiday and didn’t enter the remaining credit card charges.

Once the bookkeeper does enter the remaining credit card charges for the year, the net income of the company will be affected by the additional expenses.

So the point here is to look at the Balance Sheet. If the Balance Sheet jives with what really is in the bank (factoring in checks and deposits in transit), what inventory and equipment really exists, what really is owed on credit cards and other loans, then it is fine to look at the Profit and Loss. On the other hand, if there are glaring negatives or out-of-the-ballpark figures on the Balance Sheet, then why even look at the Profit and Loss?

Now, this is not an attempt to teach you accounting. It is simply an attempt to get a handle on whether your entries are complete and reasonably accurate. Too often people get caught up in the details and don’t know the consequences of their details. Looking at basic reports and seeing if they reflect reality is the best way to learn whether you have been entering the details correctly.

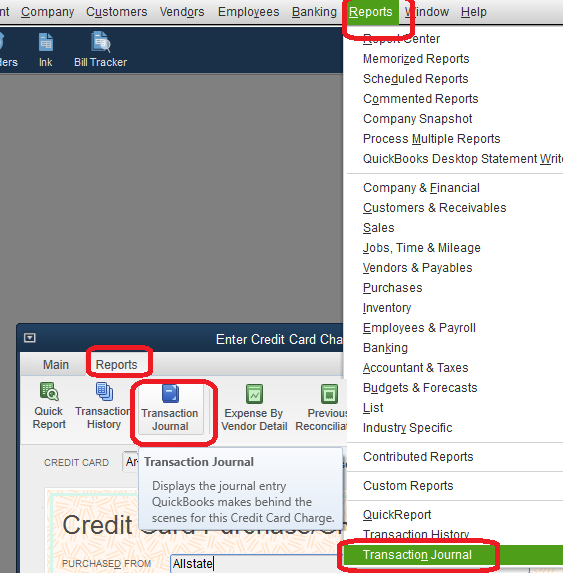

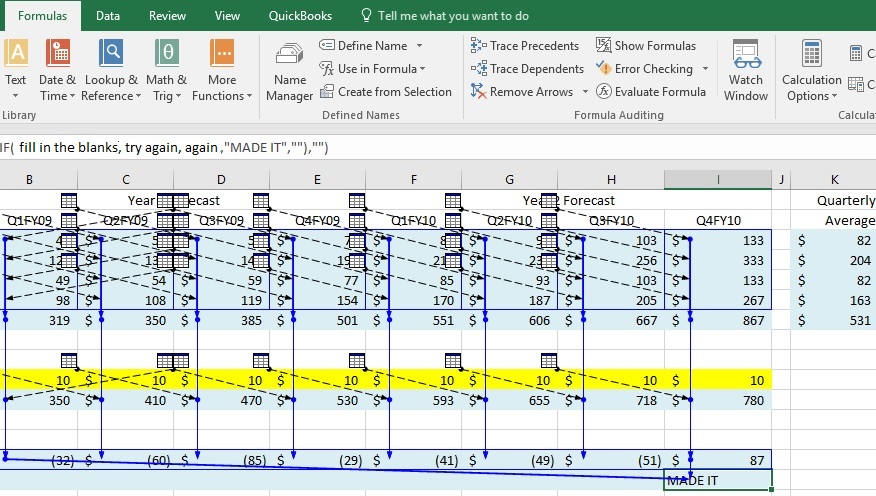

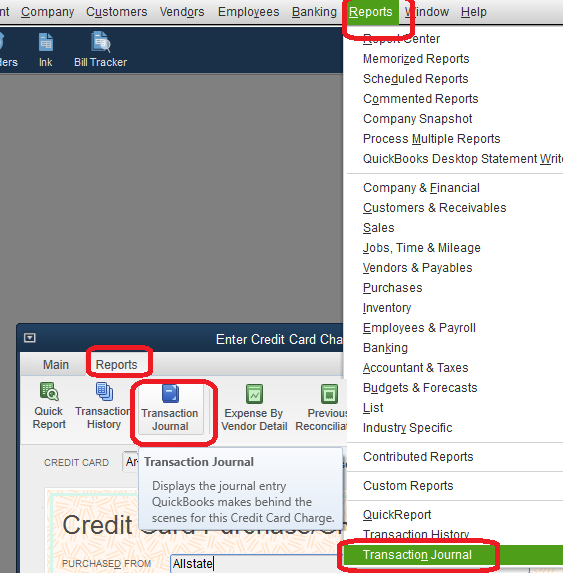

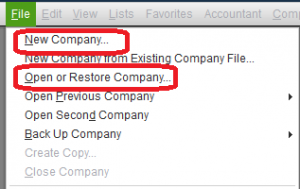

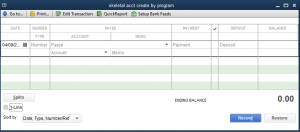

Using this concept, the concept of looking at reports to see if your entries are correct, you can begin to organically learn accounting concepts. My first bookkeeping software in the late 1990’s was Peachtree, which had a button next to every entry that displayed the transaction in a text window showing what increased on the debit side and what increased on the credit side. It was like a mini report for any transaction that I entered. I had never been formally introduced to the concept of what a debit was and what a credit was, but this was a way to experiment and learn. See if your software has this feature (in QuickBooks there is something similar: if you are in a transaction you can go to the reports menu (or in some of the newer versions of QuickBooks there is a button in the reports tab in the transaction itself):

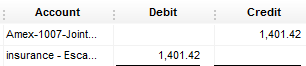

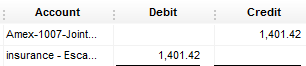

This should show you the debit and credit for the particular transaction:

If you notice, the Amex account is increasing on the right, since Amex is a liability. The insurance expense is increasing on the left, since an expense is an asset.

Of course, if you have any sense at all, you are not going to accept that an expense is an asset. Wrestle with it a little bit. Come up with arguments for and against it being an asset.

Isn’t insurance like an emergency fund, in a way? It sure is good to have when you need it. Supposedly, all expenses, assuming your goal is to make a profit, all expenses can be thought of as the subproducts and services that go into building and selling your own products to make income.

And when you convince yourself of that, then turn it around and think of examples that don’t fit. My favorite example was from the lecture I was listening to for my CPA Review. The instructor was trying to explain governmental accounting. A government decides to spend money on weapons. Is buying weapons going to bring in more revenue? “Not unless it points those weapons on the taxpayers to force them to pay their taxes.” Similarly, is spending on the elderly and disabled going to bring in more revenue? Are we creating assets with such expenditures? Or are we asking the wrong question. A government is not supposed to be a business, making profit for itself to the detriment of the people for which it is supposed to serve.

Which is why the ultimate definition of a debit and a credit is simply “debits are on the left, credits are on the right.” If assets happen to be on the left, then so be it. And if expenditures happen to be on the left along with assets, then it may or may not mean anything profound. Approach it like a scientist, see the results, experiment. When there is a concept that seems to be hard to accept, try to think about it in various ways.

Another example of a concept that throws newcomers off is that a bank account increases with debits. Pretty much all of us have received a statement or message from the bank that our bank account has been “credited” with a deposit to it, and has been “debited” by a withdrawal from it. However, in the bookkeeping software, when you look at a deposit to the bank, your own software shows it as a debit, not a credit. And vice versa for a withdrawal.

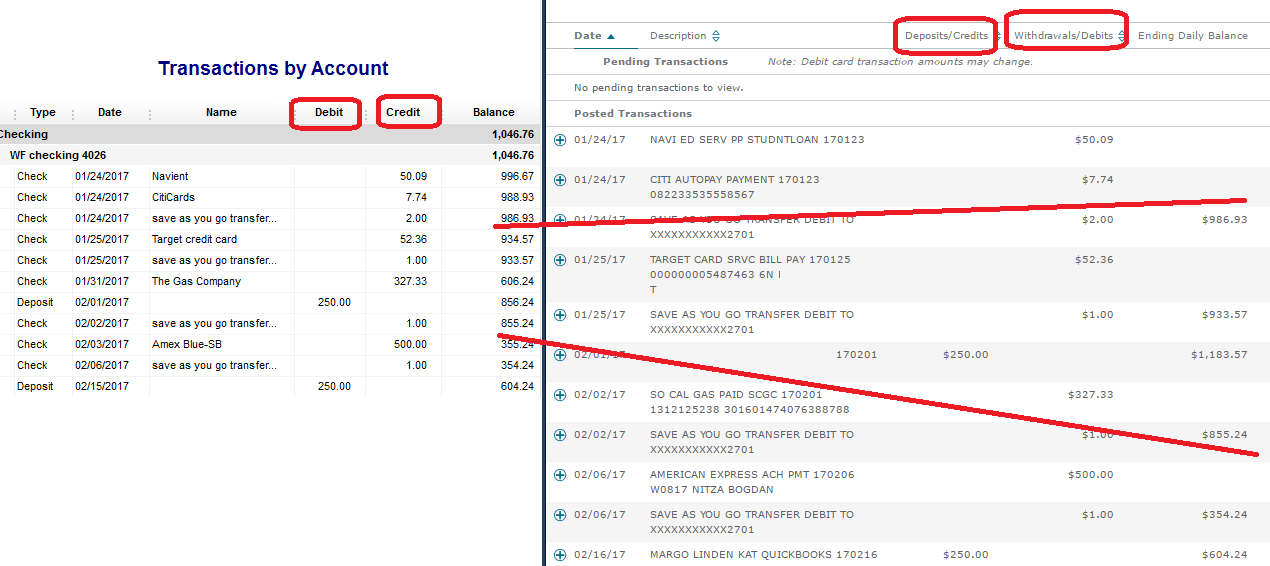

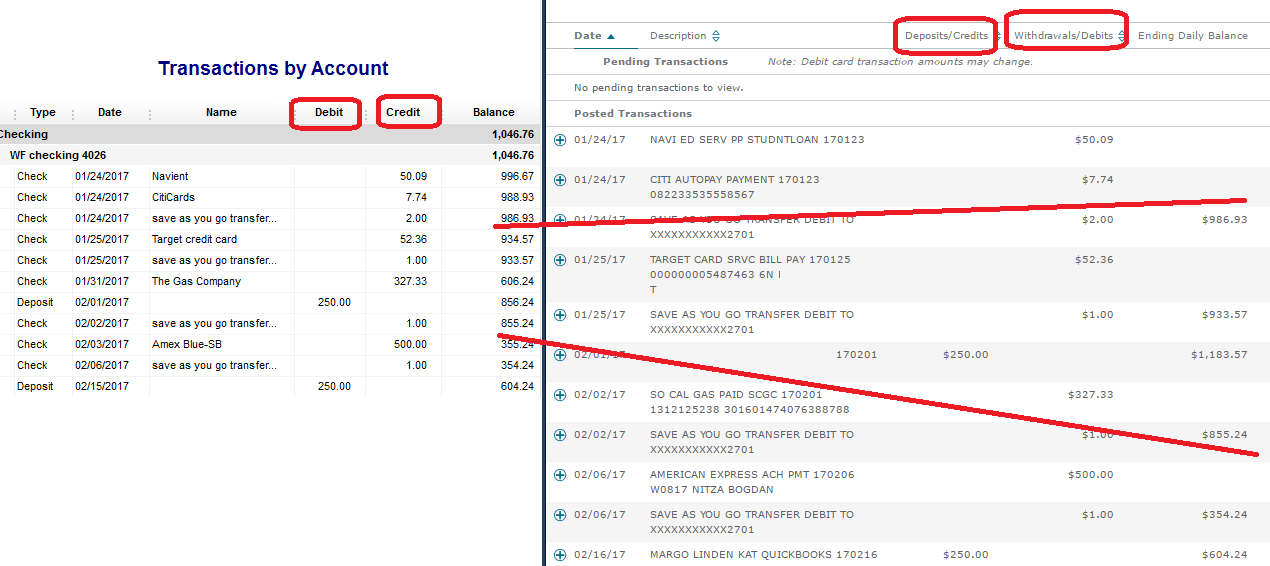

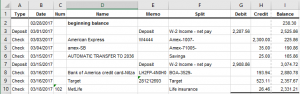

Look:

See how, in the image above, the bookkeeping software indicates Deposits=Debits and Withdrawals=Credits.

Next to it is the bank website which indicates Deposits=Credits and Withdrawals=Debits.

The reason the bank treats your deposits and withdrawals in a backwards fashion is that the money is not their money. It is your money. So when you deposit money into the bank, their liability to you goes up (credit).

Now take the case where the bank loans you money, say, in a credit card.

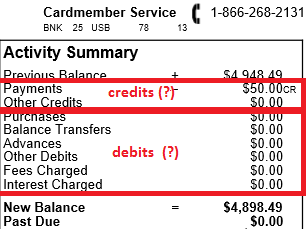

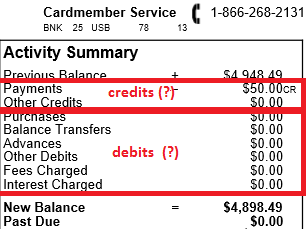

Their statement will say that the payments are credits and the purchases are debits:

The bank, loaning you money, treats their loan to you as their asset (and assets increase with debits).

If you are anything like me, when I loan money to someone I definitely do not consider it an asset. I consider it a foolish waste of my hard-earned money, knowing that I will never see it again. It may take a while to see why anyone would think of a loan receivable as an asset.

To a bank, they still own the rights to that money and they feel relatively confident that most of their loans will get repaid.

Again, your gut instincts may be fine. How can it be an asset if you know you will never see that money again (when your whining relative guilts you into lending them money, trust me, you will never see it again. It is not an asset). This is what happened in the 2008 recession. All the banks had all these “assets” (after all, when they recorded the transaction and lent the money, their bookkeepers had to debit an asset called “mortgage receivable” to record the loan). By now we know what types of loans these were. They were kiss-your-money good-bye loans that the bank would never see come back. The financial collapse was magnified because the banks kept trying to present these loans as assets.

But I digress. The point is that the banks give you pages out of their company financials. They show you their own statements, where their loans to you are their assets, and your bank accounts with them are their liabilities. You have lent them money when you deposit money into the bank, so it is your asset increasing (as a debit in your own bookkeeping software) and is the bank’s liability increasing (as a credit in the bank’s bookkeeping software).

Just remember. Debits on the left. Credits on the right. And that right and left are relative depending on which direction you are facing.

e balance sheet is kind of like the checks and balances of a government, whose function it is to give some transparency to the functions of government, and to expose lies and pretenses and the over-extension of power. It gives a trained observer the ability to see if things “add up,” and to ask questions.

e balance sheet is kind of like the checks and balances of a government, whose function it is to give some transparency to the functions of government, and to expose lies and pretenses and the over-extension of power. It gives a trained observer the ability to see if things “add up,” and to ask questions.