Big Dreams and Little Cash:

The Transfer of Negative Capital in Exchange for Services

I. Introduction.

In the early years, a startup typically runs at losses. In order to finance these losses, the company will either sell ownership interests or take on debt, or both. Tax law treatment differs depending on entity type, our focus here will be specific for partnerships. If a partnership takes on debt, it could run the risk of having negative capital. Negative capital means that if a partnership hypothetically liquidated all its assets, there would not be enough cash from the liquidation proceeds to pay off the debt.[1] A company in this situation may also be offering ownership interests to its employees to compensate for the lack of stability and lack of cash, and to motivate innovation. If the offered interest is for a share of the partnership’s net assets, the interest is called a capital interest.[2] The value of the capital interest is taxable to the recipient.[3] Proposed regulations have been released in an attempt to specify the valuation method and consequences to the recipient[4] and partnership when a capital interest is exchanged for services.[5] The proposed regulations are an attempt to settle issues that arise when following the current rules. When the capital of a company is negative, additional challenges arise when a capital interest is exchanged for services. The current and proposed regulations do not directly address the question of a transfer of negative capital in exchange for services, and so the challenge must be met by piecing together disparate rules and applying them as best we can to such a situation.

II. A Simple Example

A. Facts

To illustrate the challenge that arises with transferring negative capital, we take a simple example. A company has zero assets, $900 of debt, and two equal owners that have not put in or taken out any cash. Their initial balance sheet looks like this:

| Liabilities | 900 | ||

| Capital | Basis | Capital | Debt Allocation |

| A | 0 | -450 | 450 |

| B | 0 | -450 | 450 |

| Total Capital | 0 | -900 | 900 |

| Liabilities + Capital | 0 | ||

A and B decide to bring C into the partnership to be an equal owner in exchange for C’s services.

B. Rules

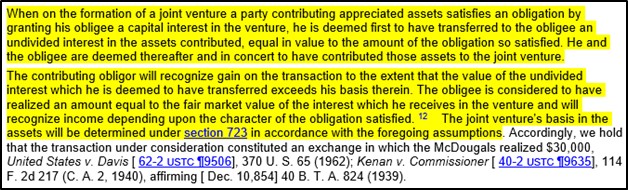

The rules specifying the steps for calculating and recognizing the amount transferred are based in case law regarding exchanging property for services[6] and several interlocking code sections that result in the following:

Step 1: Partner-to-be C provides services, or the promise of services. The partnership compensates C for her services by paying her a third of the partnership’s net assets.

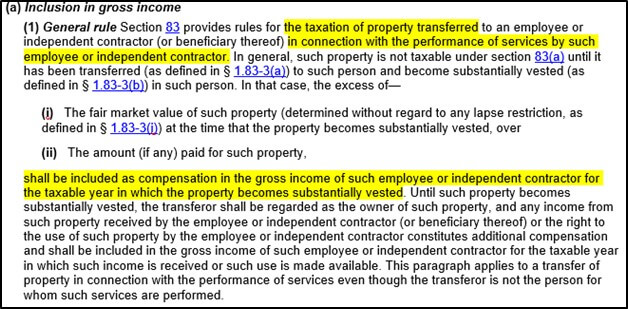

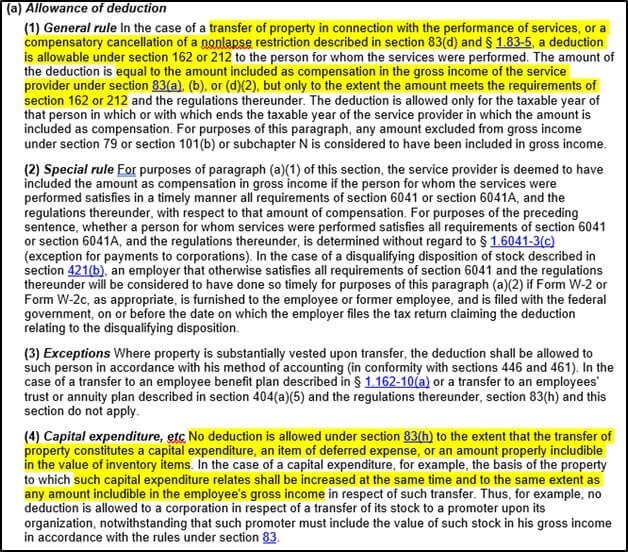

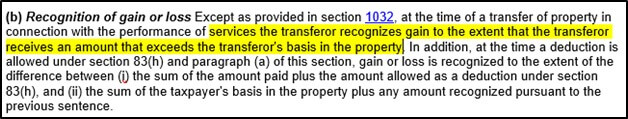

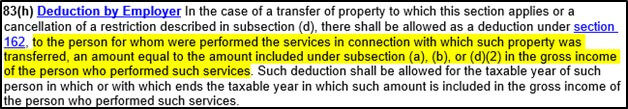

In this step, C is taxed on the compensation for services.[7] The partnership recognizes two items that affect its taxable income: (1) the cost of services (which is either deducted or capitalized) [8] and (2) the gain or loss on disposal of the net assets. [9]

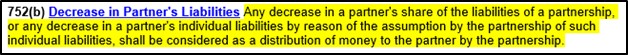

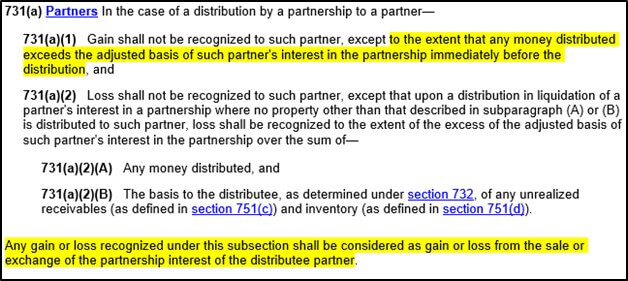

Step 2: C contributes those exact same net assets back to the partnership in exchange for a capital ownership interest.[10] If the assets are encumbered by any liability, C recognizes income to the extent that net liability relief exceeds the fair value of the assets she is contributing, since the liability relief is deemed a distribution of cash,[11] and cash distributions exceeding basis are recognized as capital gain.[12]

C. Application

Carrying out the rules yields the following result:

1. Step 1:

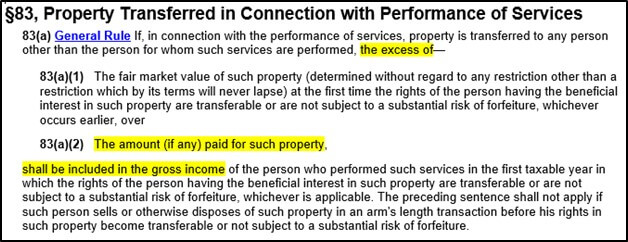

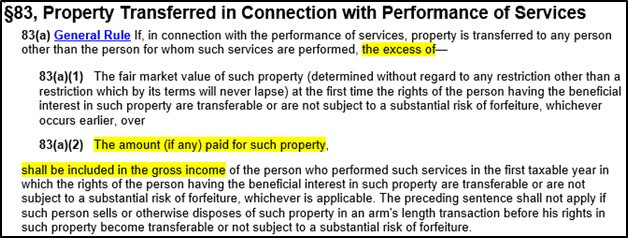

C is taxed on the compensation for services. The IRS rules calculate the amount that C must recognize as compensation as: “the excess of the fair value” of the net assets received “over the amount (if any) paid for such property.”[13] If the fair value is negative $300 and the amount paid is zero, there is no taxable income and no taxable deduction. The calculations are follows: For the fair value to be in excess of the amount paid, the fair value would need to be greater than the amount paid. Negative $300 is not greater than zero. So there is no taxable income. There is no deduction either (there is no rule here that allows a deduction for the reverse, namely paying for a capital interest in excess of the fair value, let alone when the cash paid is zero).

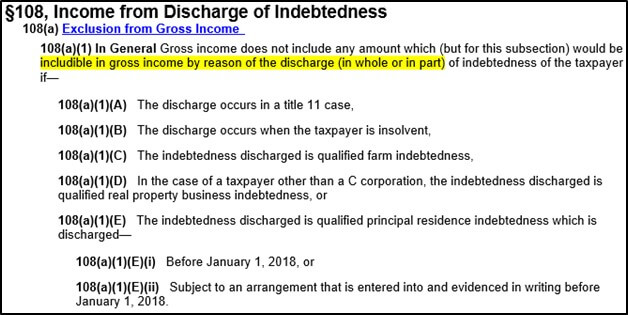

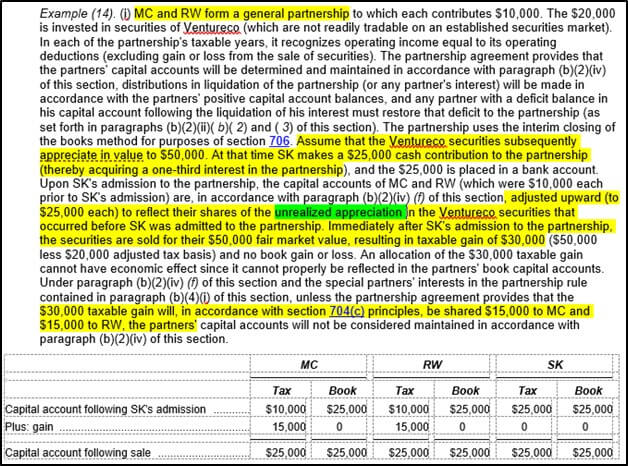

The partnership recognizes (1) the cost of services, which is defined as the amount that C recognizes as income, which is zero.[14] The partnership also recognizes (2) the gain or loss on disposal of the net assets, namely a $300 income from debt relief.[15] This $300 income is allocated to the two partners who made up the partnership before the admission of C. Note, that though the partnership recognizes this income and allocates it to the preexisting partners’ capital accounts, the rules refer to this income as “unrealized.”[16] So this is book income, no taxable income.

The balance sheet, showing both basis and capital increased by the amount of income recognized by the partnership and allocated to the partners at the end of Step 1 looks like this:

| Liabilities | 600 | ||

| Capital | Basis | Capital | Debt Allocation |

| A | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| B | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| Total Capital | 0 | -600 | 600 |

| Liabilities + Capital | 0 |

2. Step 2:

C contributes the exact net assets she received in Step 1, namely $300 of debt, back to the partnership. In doing so, C is relieved of the $300 debt handed over to the partnership while taking on responsibility for $300 of debt allocated to her out of the $900 partnership’s total debt. The net liability relief to C is zero, so C doesn’t recognize income for debt relief.[17]

Partners A and B witness the partnership liabilities increase from $600 to $900. A third of the total liabilities gets allocated to C as her right as a one third partner, the result being that the entire increase in liabilities ends up being allocated to C.

But what happens to the capital accounts? As you can see in the balance sheet below, liabilities have increased while capital has remained unchanged — and there are still no assets. (The reason capital stays the same is because capital is only increased by recognizing income or by capital contributions and is only decreased by recognizing losses or by capital distributions. [18] There is no income and no loss recognized in Step 2, and no infusion or distribution of capital in Step 2.) The balance sheet is out of balance. (Liabilities plus capital are supposed to add up to zero if there are no assets, and yet here they are adding up to $300.) The cause of the out-of-balance? C’s overpayment (zero) over the fair value of the net assets (negative $300) in Step 1. This overpayment was ignored at the time, since there wasn’t any specific rule addressing it in the context of transferring a capital interest in exchange for services.

The Balance Sheet at the end of Step 2:

| Liabilities | 900 | ||

| Capital | Basis | Capital | Debt Allocation |

| A | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| B | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| C | 300 | 0 | 300 |

| Total Capital | 300 | -600 | 900 |

| Liabilities + Capital | 300 |

There are of course further code sections that can be utilized that will eventually resolve the above situation. The analysis is only just getting started. We will need to go back to step B, find more rules that are applicable, and apply them.

III. An Approach to the Problem

The Internal Revenue Code is like a map, showing step by step, branching, back-tracking, merging, diverging routes. There are overarching rules to provide general guidelines, there are procedural rules to give specific guidelines, and there are anti-abuse rules to give micro-managing guidelines. As we look at this map, there are so many paths we can easily mistake one for another and not realize we are heading in the wrong direction.

So the first step to the approach is to step back and look for landmarks. When using a map, there are two places that are helpful to have in mind.

The first is: where are we? The second is: where do we want to go?

If a company transfers negative capital in exchange for services, for a capital interest in a partnership, what are the tax consequences?

That is where we want to go.

We are loath to divert off course, to arrive at a profit interest in a partnership instead of a capital interest, to exchange positive capital instead of negative capital, to check out capital in exchange for property instead of in exchange for services. Those are all for a different day, a different goal.

We might check out competing routes that are marked as short cuts, and as detours around accidents: proposed regulations, commentary, and innovative applications. If they offer a route that will resolve negative capital, in exchange for services, for a capital interest, we are willing to try them out. But first, where are we?

A. What Is Our Starting Point?

How did we get here? Why are we interested in this? What kind of situation are we in? Whenever learning something, think why is it relevant. Very well, a little backstory to orient us.

It all starts with school. When discussing negative capital, it helps to start with school. Well, a couple years ago there existed a school that decided to graduate a young MBA who decided to start a company. Or perhaps, more likely, what happened was this: he was assigned a project for homework: go start a company, he handed in the assignment, he got an A and graduated, and then found himself released to the streets.

Where were we during all this? We were minding our own business, in an accounting office of course, safely far away from the escaped MBA graduate.

Then in barges this young graduate, together with his cofounder of his new company. We look at the financials. We look at the LLC operating agreement. We look at the operating agreement’s exhibit A. And we look at the attendant vesting schedule for all those developers.

We glance back at the financials. If you can call them that; they are more just a list of expense transactions. There’s pet food and toiletries mixed in them.

We glance back at the operating agreement. The initial capital contributions on exhibit A are all “Services in Lieu of Cash” and all the vesting interests are specified as capital interests. No member is responsible for any debt. No member is obligated to restore any negative balance in their capital account. No member is obligated to repay the capital contributions of any other member. All distributions, allocations, everything will be done in exact accordance to the ownership interest. Looks good.

We look at the financials again. The expenses are outweighing the income. This loan to the company from Founder 2, is it ok to consider that a capital contribution? No, that is a loan, otherwise it would throw off everyone’s ownership interest percentage.

This vesting agreement, each year another percentage vested, another percentage ownership of capital transferred from the two founders to the vesting developers. What is going to happen in year two, when you two founders transfer portions of your negative capital. To these others. In exchange for services. For a capital interest in the partnership?

What’s going to happen? Our ownership percentage will go down and theirs will go up, of course!

And then we are lost.

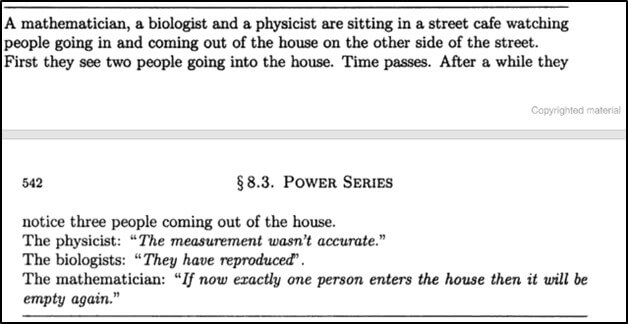

We stop for a moment here to ponder an existential riddle: Three accountants are stumbling through a snowstorm in the wilderness, and they see up ahead an abandoned, empty hut, the wind howling through it, the door hanging off its hinges and swinging wildly. Before they can reach it, they observe two people stumble up from the other side of the woods, go in, shutting the frail door behind them. A few moments later, the door opens and three people burst out and take off running. The three accountants stare, dumbfounded. Then the first accountant says, “we must have made a mistake. They must not have disclosed there was a person in there to begin with.” The second replies, “not necessarily. They must not have disclosed that they had a baby while in there.”

The third says, “I don’t see what you two are upset about. They’re just planning for one more person to go in so it will be empty again.”[19]

Ok, enough already, it is getting cold. We approach the hut. And as we get closer, we see something rustle in the wind, it appears to be a map that one of the strangers dropped.

B. What Are the Issues?

The map has boxes and lines, arrows and words. We skim over it and see:

IRS map landmark number 1. What is negative capital?

There is that school on the map here. Perhaps there is a dictionary or a math or history book in this school that will explain. Or perhaps a crushing student loan. Or a disruptive student. We shall have to check it out.

IRS map landmark number 2. Does it matter that the interest is exchanged for services rather than for property?

Yes, property seems to be depicted by nice gated communities. Services veer off into the wild.

IRS map landmark number 3. Does it matter that the interest is a capital interest rather than a profit interest?

Yes, the path in the wild splits, with profit interests continuing along a nice hike with blazed trees. Capital interests lead straight to an unfordable river.

IRS map landmark number 4. Does it matter what kind of services are being exchanged for the capital interest?

The profits interests paths splits, though a couple faint paths veer off from the nicely marked trail (deer paths?) to meet up with the capital interest path at the foot of the unfordable river.

IRS map landmark number 5. Do we need to know the value of the capital interest in and of itself?

There is a rickety bridge over the raging river. This bridge is the value of the capital interest. Yet there seems to be some sort of troll under the bridge. And some danger signs about high winds.

IRS map landmark number 6. Do we need to know the value of the service in and of itself?

This path side-steps the bridge and the troll, ending up in a dead end a little further up river. But there is one dotted line that seems to cross the river. It is uncertain what that dotted line is. A path of desperation, no doubt.

IRS map landmark number 7. Does it matter when the capital transferred?

There seem to be some parts of the bridge that look a little more dangerous than others, depending on when and how often the capital is being churned over. But all the paths eventually lead to the other side.

IRS map landmark number 9. What is the tax basis of the capital received in the hands of the new partners in year 2?

A second river. Bigger than the first. No bridge. Just a row boat to rent. There is a makeshift structure on the banks of the river. The map just has an arrow pointing to it. No paths lead out of it. It looks familiar. We are here at the abandoned, empty hut in the snowstorm. Or perhaps it is worse than empty. Perhaps it will swallow one of us alive in order to become truly empty.

IRS map landmark number 10. Are any partners receiving liability relief upon the transfer of their negative capital?

What a ridiculous question. Did we not read that no partner is responsible for any debt? The operating agreement specifically said the debt belongs to the company, not to any member. However, strangely enough, the map shows the boat to use to cross the river is this landmark.

Ok, so now that we have discussed the facts, identified the issues, let’s look at how the rules apply to each of these issues.

C. What Are the Rules?

IRS rules applicable to issue 1. What is negative capital?

The reason there is an image of a school here is because at first blush a school is a terrible thing to spend money on. Children can’t work in the fields when they are in school. The cost of paying for the school plus the loss of child labor creates an unsustainable enterprise. Besides, children don’t even like school. However, communities and governments or whoever is paying for the school seem to think it has some value… in the long run. The thinking is, the money and time spent on school will somehow pay off in the future.

So what appears to be a negative, quite possibly is really a positive, just the timespan needs to be lengthened out. Just because the IRS insists that all money in and money out be measured once a year doesn’t mean that a year is enough time to convert the money out into money in.

The thinking is, there is a work in progress somewhere. The work in progress cannot have value to customers until it is complete, so it is not (usually) assigned any value. Once it is complete and a customer has bought it, all will be fine, so a little bit of temporary negative capital is, in retrospect, ok.

Differentiate here between negative capital and negative basis. Capital is allowed to go negative due to losses. It is a tally of sorts, showing how much is required to break even after debts are paid back.

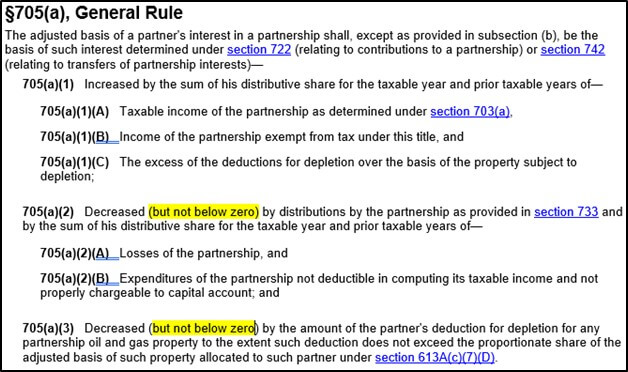

But the basis in the capital is not allowed to go negative.[20] A negative capital avoids a negative basis by suspending the losses that brought the capital below zero. As long as no cash is distributed, the suspended loss waits for the day when the profits are sufficient to absorb it.

Basis is the concept of the amount paid to purchase something. If someone “paid negative dollars for the capital,” it would mean that they consummated the purchase by receiving money, rather than by paying money. If money is received, unless the recipient is somehow on the hook to pay it back, or to pay that amount of the company’s debts back, the amount bringing the capital below zero is considered income, and taxed. This only occurs when a cash distribution is involved. The amount recognized as income is deemed to bring the basis back up to zero.

IRS rules applicable to issue 2. Does it matter that the interest is exchanged for services rather than for property?

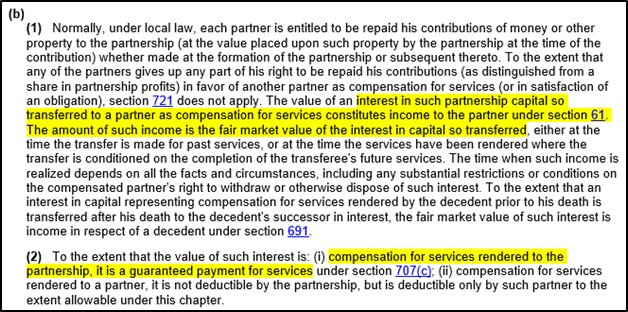

Property has special treatment by the IRS. The IRS map shows that property contributed to a partnership in exchange for a partnership interest creates a capital ownership in the company based on the fair value of the property, and does a pretty good job ensuring that the appreciated value will not be taxed upon receiving a capital interest.

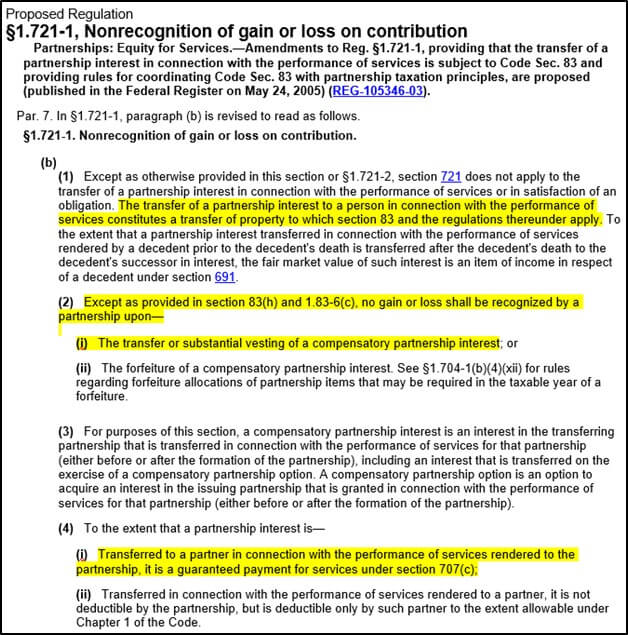

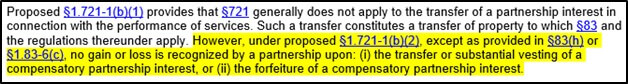

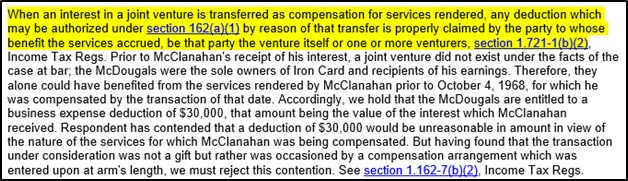

Services is a different story. A partnership interest is commonly considered property, and the IRS as a general rule treats services exchanged for property as a taxable event. There are some exceptions, as we shall see as we continue along this path.

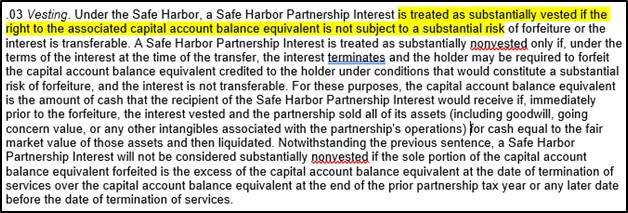

IRS rules applicable to issue 3. Does it matter that the interest is a capital interest rather than a profit interest?

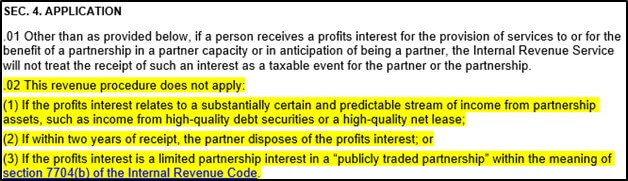

A profit interest has special treatment by the IRS. The IRS acknowledges that it is hard to predict what profits will be, and so as a practical matter allows the speculative value to escape untaxed. The map shows this treatment is still in the wilds, but it is pretty tamed wilds by now. It has taken many years to achieve a nontaxable treatment for profits interests, and if unwary, a profits interest may be taxed like a capital interest.

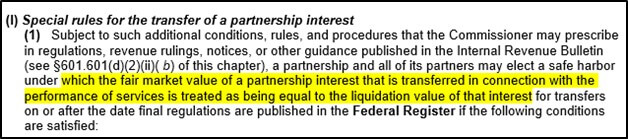

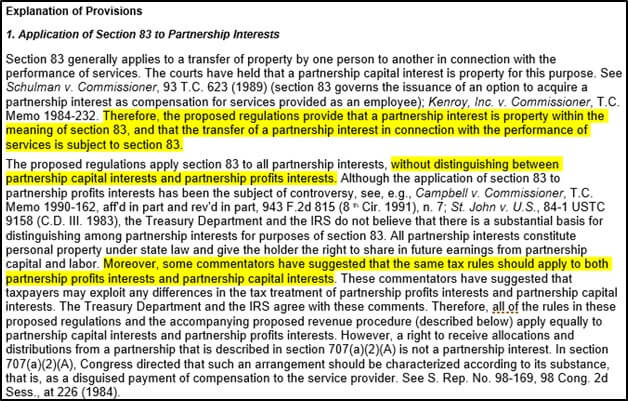

Interestingly enough, the proposed regulations put forward a framework whereby the differentiation between a profits interest and a capital interest is irrelevant. “The proposed regulations apply section 83 to all partnership interests, without distinguishing between partnership capital interests and partnership profits interests.”[21]

IRS rules applicable to issue 4. What kind of services are being exchanged for capital interest?

One of the traps for the unwary lies in whether a profits interest is earned in exchange for services performed in anticipation of being a partner (management decision type services), or whether the services were performed as an employee/subcontractor (technical or mechanical type services). Since this distinction only effects profit interests, and since our issue is regarding a capital interests, this may be irrelevant to our path, but it is interesting that some leg of the profit interests has lost its non-taxable status and joined up with our path in such a circumstance.

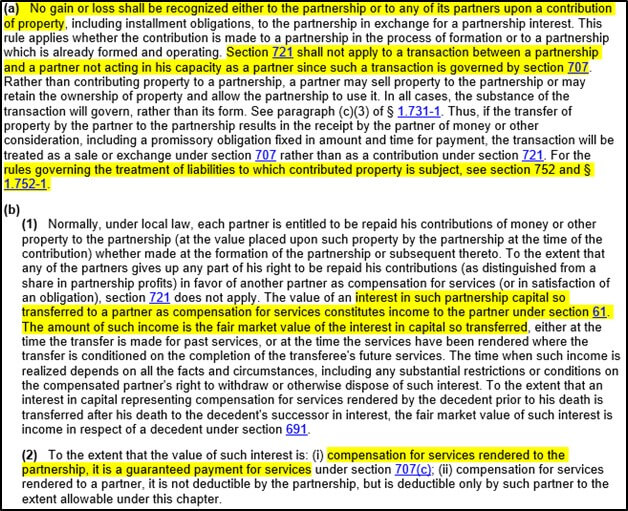

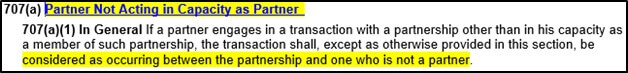

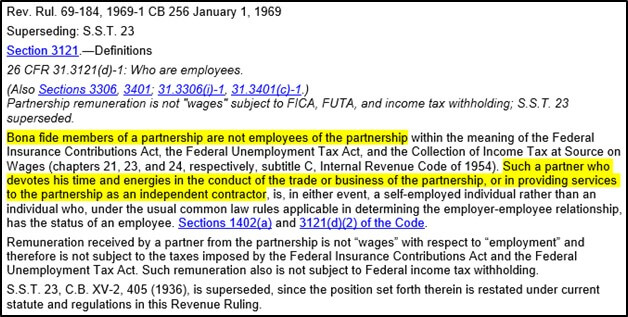

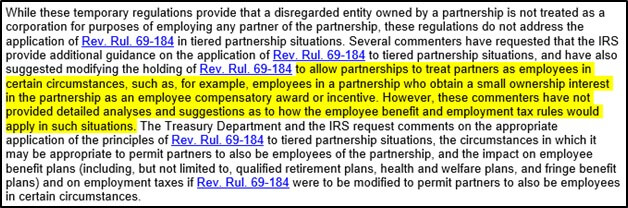

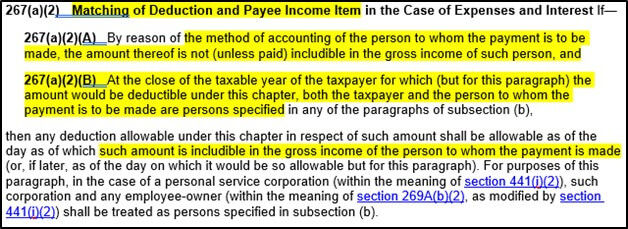

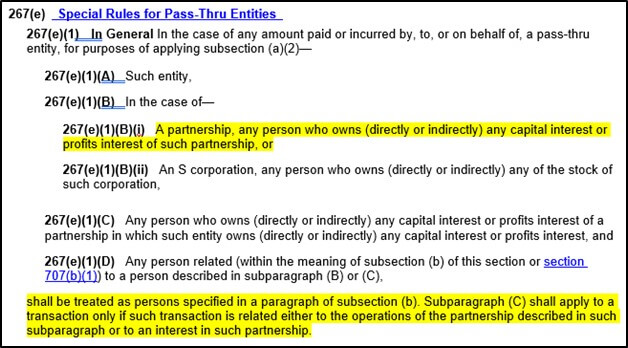

The IRS Code differentiates different tax treatment for different kinds of services. Compensation for a service that is NOT in the capacity of a partner is treated the same way as any service paid for on the open market is treated.[22] It gets reported on a 1099 if it is provided by a subcontractor, or it gets reported on a W2 if it is provided by an employee (although the IRS doesn’t allow a “bona fide” partner to be treated as an employee,[23] there is debate regarding the treatment of an employee of a partnership who receives incentive partnership interest options[24]). The partnership will be able to either deduct it or capitalize it, whichever is appropriate,[25] however, if the partnership wants to deduct it, the timing of the deduction is dependent on whether the recipient is cash method or accrual method.[26]

Compensation for a service that IS in the capacity of a partner is treated as either a guaranteed payment or a distribution of profits. If the form of compensation is an interest in the partnership, and if the compensation is taxable, it is always treated as a guaranteed payment.

IRS rules applicable to issue 5. Do we need to know the value of the capital interest in and of itself?

If we have come to this point, and all paths point to the interest in exchange for services to be taxable as income to the recipient, the IRS rule is that the amount of income is determined by the fair value of the capital interest. [27]

IRS rules applicable to issue 6. Do we need to know the value of the service in and of itself?

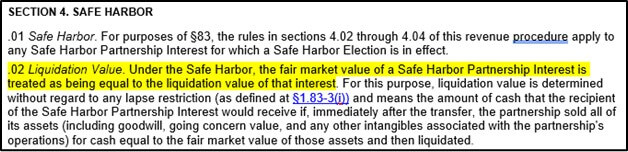

No. Remember, this was a dead end on the map. What matters is the value of the interest received. Which is why profits interests can be often analyzed as having a zero value: on the day that a profits interest is granted, by definition no rights are given to the assets in the company. Only after time elapses and the profits accumulate does it have any value. The IRS map has blazed a trail with safe harbor rules specifically exempting most profits interests from taxability.

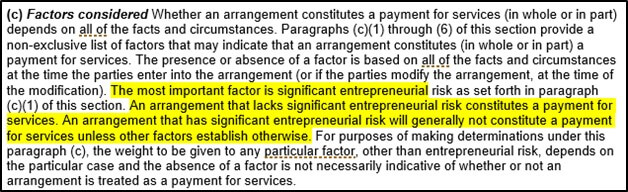

The capital valuation in the example case of negative capital can mirror the valuation of a profits interest – if the only value is the hope of better days to come, the value on the particular day it is granted is often speculative. If someone was taxed on their usual living wage, as would be the case if the IRS rule was to tax the compensation on the value of the services instead of the value of the capital interest, it would be at odds with the allowance the IRS provides for not treating as compensation the income derived by “entrepreneurial risk.”[28]

But before we discount the possibility of valuing the compensation based on the usual price of such services, let’s take one last look at the map. Remember – there was some strange dotted line across the river here. Perhaps in some cases the value of the services is used to determine the amount of income to be recognized by the recipient, rather than the value of the partnership interest. And indeed, there are times when the courts determine the most objective valuation method is using the cost of services, absent any other measurable item.

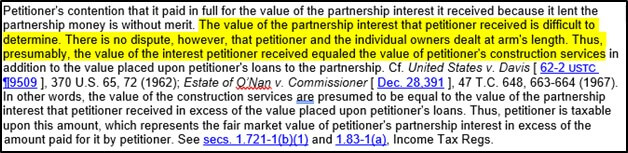

The issue is of valuation of the capital interest. If the capital interest obviously has a value, an appraisal of that value can include the normal cost of creating a thing of similar value. In Phelps v. U.S., the courts consented on the difficulty of valuation with the following statement, and the reason for resorting to the value of the services in and of themselves:

The value of the partnership interest that the petitioner received is difficult to determine. There is no dispute, however, that petitioner and the individual owners dealt at arm’s length. Thus, presumably, the value of the interest petitioner received equaled the value of petitioner’s construction services. [29]

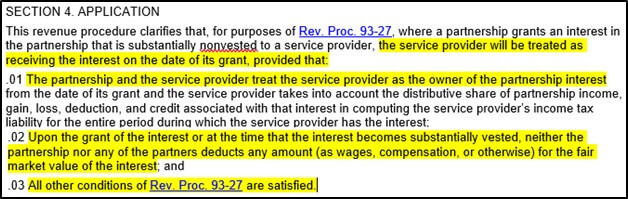

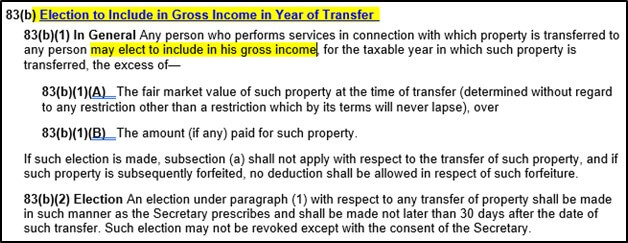

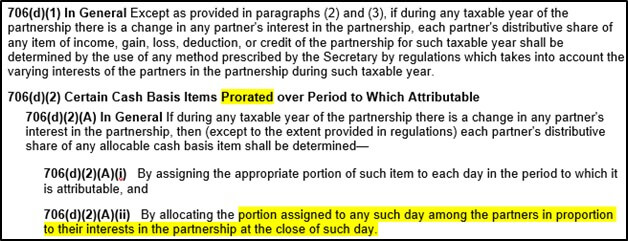

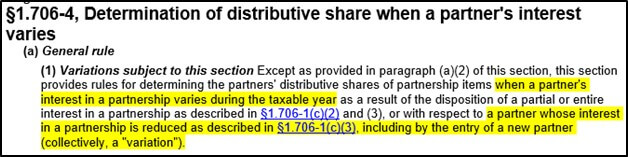

IRS rules applicable to issue 7. Does it matter when the capital transferred?

Well, it does matter, because the value can change wildly from month to month, and if it is taxable as income based on the value of the interest, then that value must be evaluated on the moment the interest is transferred. Because at the moment in time that a profits interest is granted, there are no rights to the assets, the valuation is zero on the day it is granted. [30] Before the IRS spelled out safe harbor treatment, and specified that a profits interest is considered as being transferred on the day it is granted, not the day it vests,[31] there was some confusion as to what value it had – the zero value on the day of grant or the-end-of-vesting period value. If an interest is not a profits interests that falls under the safe harbor rules, a special election needs to be made in order for the value of the interest to be on the day of grant rather than when the interest is fully vested.[32]

Once it is figured out what day an interest is transferred, the ownership must be weighted for purposes of allocations.[33]

IRS rules applicable to issue 9. What is the tax basis of the capital received in the hands of the new partners in year 2?

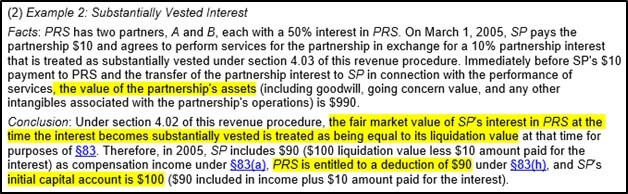

The new partners are considered to receive, and be taxed on, an amount based on the value of the capital interest. But what is that value? Here we come to the troll under the bridge, because an appraisal of a start-up company’s value, in its early years, even when income is actively being generated, is difficult. The company has yet to make a name for itself or iron out its kinks, a lot of it is still a work in progress. Proposed Regulations give the simplest method of the valuation by using the liquidation valuation method. If all assets are liquidated on the moment the interest is granted, how much is the recipient entitled to?[34]

In this case, the company has no assets, it just has a loan from Founder 2 and negative capital accounts from the remaining partners, who are not on the hook for any loan upon liquidation. So, the basis in their newly received capital accounts must be zero. Or is it?

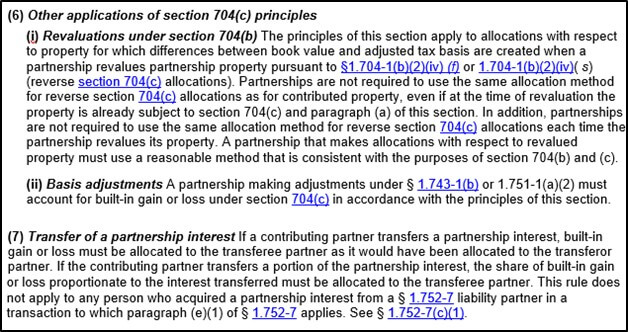

We should be grateful that in this scenario the basis is zero. If there had been some value in the assets, the assets would have been treated as if partially sold, and the gain on the sale would have been allocated to the other partners, and the asset would have been deemed to have been contributed back.

IRS map landmark number 10. Are any partners receiving liability relief upon the transfer of their negative capital?

So here is where we look at the consequences on liquidation to each of the members with negative capital. None of them have a negative capital restoration agreement (meaning none of them are required to chip in money when their account goes negative). None of them have responsibility to take on any debt. So, Founder 2, who loaned money to the company, just realized a bad debt expense with respect to the company. Remember, the operating agreement specifically said that all debt belonged to the company alone. Consequently, the company realizes cancelation of debt income. This income is shared equally by all the members, including the newly minted members. The old members all had suspended losses to absorb the income and come out at zero. The new members upon the theoretical liquidation on the moment they received their capital interest, started at zero basis, were allocated income equal to their vested percentage, and received no cash, and so got taxed on ordinary income and recognized a capital loss.

IV. The Unbalanced Balance Sheet

Let’s get back to our original illustration of our simple A, B, C service partnership, now that we have oriented ourselves a little more to what our question really is about. Our illustrative example of a small hiccup that might occur in the following of the rules regarding exchanging negative capital for cash left us with the capital account being $300 too little (or should we say $300 too much, since it is negative numbers we are dealing with).

Here again was the balance sheet where we left it last:

| Liabilities | 900 | ||

| Capital | Basis | Capital | Debt Allocation |

| A | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| B | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| C | 300 | 0 | 300 |

| Total Capital | 300 | -600 | 900 |

| Liabilities + Capital | 300 |

The answer lies in the IRS rule about admitting a new partner to a partnership. When a new partner is admitted, the capital accounts must be “booked up” to reflect the fair value of the net assets. And here, after the partner got admitted, the new fair value of the company is negative 900 (the value of the liabilities). The capital account needs to be adjusted to reflect the fair value of the net assets. This fair value bookup is the bridge with the troll under it. The troll is our natural aversion to marking things up to fair value.

An accountant, unless trained to be an appraiser, is not an appraiser. Regarding the requirement for an accountant to make estimates of value, Robert Sterling, in this book “Theory of the Measurement of Enterprise Income,” says, “[Accountants] were not much more than specialized craftmen when an almost overwhelming responsibility was rather suddenly thrust upon them.” He goes on to describe:

The accountant passed through the era of swashbuckling manipulation; the era of watered stock and financial bubbles; in short, the era of chicanery by financial overstatement. In addition, he has always been faced with the effervescent optimism of the entrepreneur.

Accountants, apparently, prefer solutions which “are accepted and rather rigid.” If asked to provide their own theory about valuation, accountants will probably take a whole block quote from an authoritative source rather than venture their own guess.

The most widely accepted rule of valuation is said to be ‘historical cost’…. Occasionally, there is some difficulty in obtaining the cost figures, and the accountant reverts to conservatism by making a rather low estimate or, if the amount is “immaterial,” by assigning a zero value.[35]

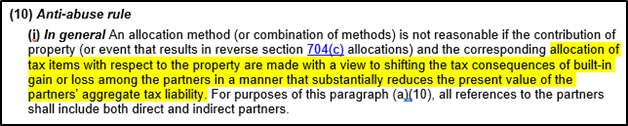

The IRS rules, however, require a bookup of assets to fair value when a new partner is admitted,[36] the most pressing concern on the part of the IRS is in order to prevent income shifting,[37] however, as a secondary reason, in order to that the maintenance and allocation of the capital accounts properly reflects the operating agreement.

In our example of the three equal partners, the agreement between the partners specifically promised that each partner would be an equal sharer of capital upon the transfer of the capital interest to C:

| Liabilities | 900 | ||

| Capital | Basis | Capital | Debt Allocation |

| A | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| B | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| C | 300 | 0 | 300 |

| Total Capital | 300 | -600 | 900 |

| Liabilities + Capital | 300 |

The capital represents the net assets which is negative 900, not negative 600. C is missing a share of capital. Once it is given to her, all is in balance again:

| Liabilities | 900 | ||

| Capital | Basis | Capital | Debt Allocation |

| A | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| B | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| C | 0 | -300 | 300 |

| Total Capital | 0 | -900 | 900 |

| Liabilities + Capital | 0 |

Now this leaves an uncomfortable feeling when beginning someone’s capital at a negative number, but it does give a simpler picture of what occurred. Partners A and B recognized relief of liability in the amount of $150 each. Partner C came in as an equal partner. If the partnership liquidated today, A, B, and C would recognize cancelation of debt income of $300 each and the company would close. C may know enough to trust that the company will be able to weather the early losses and will reach and overcome the make-break point soon enough.

Proposed Regulations eliminate the problem of the out of balance Balance Sheet by stipulating that the partnership should not recognize gain upon the transfer of net assets in Step 1.[38] Without recognizing gain, the liabilities would have remained at $900 and C wouldn’t have had a $300 excess of price paid for an interest over its fair value that she left out of the equation, and the re-shuffling of liabilities would have still given the same effect: A and B recognizing $150 each of income due to relief of liabilities and C helping out with the liabilities.

Proposed Regulations also give accountants a sigh of relief in that the definition of Fair Value is simply the liquidation value on the day the partnership interest is transferred. This eliminates some complicated valuation techniques such as forecasting the present value of future cash flows. The example we have worked through assumed that not only the capital but also the fair value actually was negative, but just because the capital is negative doesn’t mean the fair value has to be negative. A business appraisal might value such a company at 30 million dollars. If this were the case, a new asset would need to be put on the books for goodwill and going concern value, and each partner would need to be allocated it according to the operating agreement. It may cause some cash flow problems for C to be given a W-2, or 1099, or allocated a guaranteed payment (no matter which, it would be capitalized and not deducted by the partnership) for ten million dollars. And how would the appreciation of the business value be allocated? Only to A and B, in the same way that appreciated value customarily is allocated to the pre-existing partners as if it is their creation? What if C is the value that will create the future cash flows?

IV Recommendation

For anyone who finds themselves in the situation of having to assign a value to negative capital, step back. It is a mind-blowing concept to conceive that an entity has any value more than what it costed, or that it has a value of below zero even if that IS what it costed. And after we do entertain the notion that a value may exist that is more than cost, or less than zero, we have to instruct the client to go and find out that value, because it is not within our ability to do so. We have three scenarios: the client has not disclosed the value that makes it attractive to buyers, there are works in progress that about to birth value, or there is a vacuum waiting for the next sucker to join.

V. Expanded footnotes:

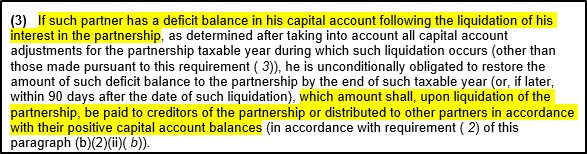

- Definition of negative capital: Reg. §1.704-1(b)(2)(ii) discusses consequences of a deficit balance in any one partner’s capital account, in terms of liquidation and obligations to creditors, the concept of deficit capital for a partnership as a whole can be inferred from this.

- 1.704-1(b)(2)(ii)(b)(3):

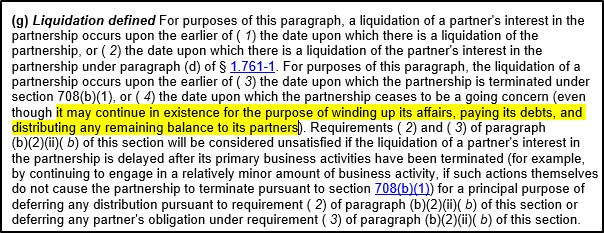

- 1.704-1(b)(2)(ii)(g):

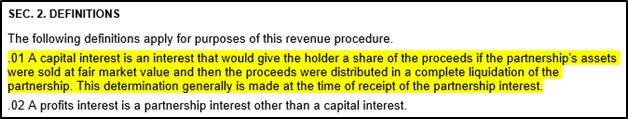

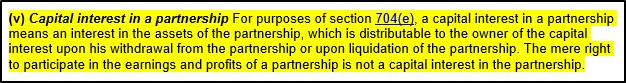

- Definition of capital interest: Rev. Proc. 93-27, 1993-2 C.B. 343; Reg. §1.704-1(e)(1)(v)

Rev. Proc. 93-27, 1993-2 C.B. 343

Reg. §1.704-1(e)(1)(v)

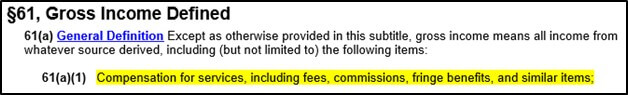

- The value of a capital interest is taxable to the recipient: R.C. §61; I.R.C. §83(a); Reg. §1.721-1(b)(1)

I.R.C. §61

I.R.C. §83(a)

Reg. §1.721-1(b)(1)

- Proposed valuation method and consequences to the recipient: Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221; Prop. Reg. §1.83-1(l)

Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221

Prop. Reg. §1.83-3(l)

- Proposed consequence to the partnership: Prop. Reg §1.721-1(b)(1); REG-105346-03

Prop. Reg §1.721-1(b)(1)

Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221

- Case law regarding exchanging property for services: McDougal, 62 TC 720 (1974)

McDougal, 62 TC 720 (1974)

- The recipient is taxed on the compensation for services: Treas. Reg. §1.83-1(a) (2003)

- The partnership recognizes the cost of services: Treas. Reg. §1.83-6(a) (2003)

- The partnership recognizes the gain or loss on disposition: Treas. Reg. §1.83-6(b) (2003)

(Note: the proposed regulations stipulate the partnership does not recognize gain or loss on disposition. See footnote 5, supra.)

- The new partner contributes assets to a partnership in exchange for a capital ownership interest: Treas. Reg. §1.721-1 (2011)

- Liability relief is deemed a distribution of cash: I.R.C. 752(b)

- Cash distributions exceeding basis are recognized as capital gain: I.R.C. §731(a)

- The amount the recipient recognizes as compensation: I.R.C. §83(a)

- The partnership measures the cost of services as the amount that the recipient recognizes as income: I.R.C. §83(h)

- The partnership recognizes income from debt relief: I.R.C. §108(a)

- The income would be allocated to the pre-existing partners: Treas. Reg. §1.704-1(b)(5) Example (14)(iv)

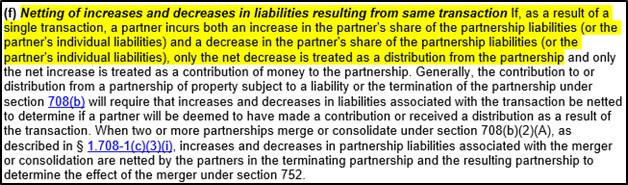

- Debt relief is measured after netting the liabilities contributed with the liabilities assumed: Treas. Reg §1.752-1 (f)

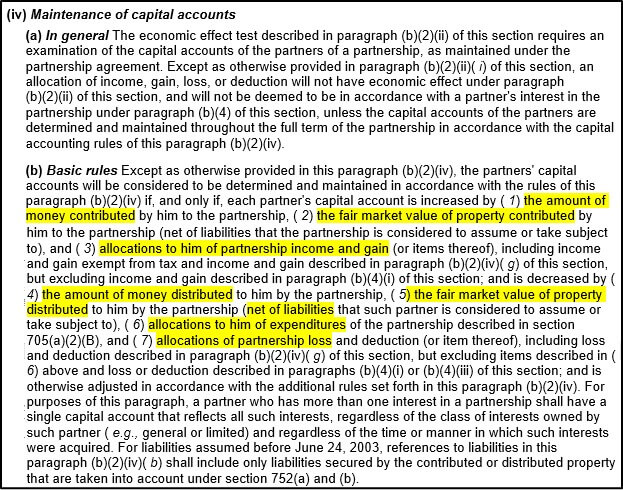

- Capital is increased by income and contributions, decreased by losses and distributions: Reg. §1.704-1(b)(2)(iv)

- “Infinite Series and Power Series.” Calculus with Maple Labs: (Early Transcendentals), by Wieslaw Krawcewicz and Bindhyachal Rai, Alpha Science International, 2003, pp. 541–542, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=16MjPAH_CBYC.

- Basis is not allowed to go negative. §705(a):

- Proposed regulations intentionally don’t distinguish between capital and profits interest: REG-105346-03 (2005)

- Compensation for a service not in the capacity of a partner: I.R.C. 707(a)(1)

- “Bona Fide” partners not allowed to be employees: Rev. Rul. 69-184, 1969-1 C.B. 256

- Debate regarding the treatment of incentive partnership interests for employees: T.D. 9766, 81 Fed. Reg. 26693 (5/3/16)

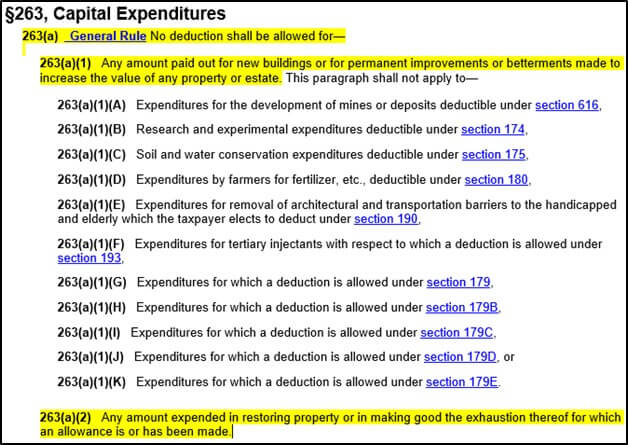

- The partnership will be either to able to deduct it or capitalize to cost of services: I.R.C §263

For deducting the services, see I.R.C. §83(h), in footnote 14, supra)

- The timing of deductions made by a partnership to a partner: I.R.C. §267(a)(2) and (e)

- The value of a capital interest is taxable to the recipient: I.R.C. §61; I.R.C. §83(a); Reg. §1.721-1(b)(1)

(see footnote 3, supra.)

- Arrangements that has significant entrepreneurial risk is not compensation for services: Reg. §1.707-2

- Hensel Phelps Const. Co. V. United States, 413 F.2d 701 (1969)

- The safe harbor rules for a profits interest to be considered nontaxable: Rev. Proc. 93-27

- Proc. 2001-43, (8/2/2001)

- R.C. 83(b)

- Weighting interests to account for variation in ownership: I.R.C. §706(d); Reg. §1.706-4

- Using liquidation value as the valuation method: Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221

(see footnotes 5 and 21 for REG-105346-03 70 Fed. Reg. 29675 (5/24/05))

35.

VI. Epilogue.

This paper was about a real client, new, who, two and a half years ago, came to our accounting office with his co-founder friend to ask us to prepare their company’s tax return. After puzzling over the finances, capital structure, and vesting schedule, we asked: “What is going to happen in year two, when you two founders transfer portions of your negative capital?” We were given a strange look, as if we had asked a question with the most obvious answer. We prepared the partnership’s Year 1 return, but the following spring we told the client they would need to pay for the Year 1 return before we could prepare the Year 2 return. And so the client was forced to find another accounting office.

I too left the accounting office around the same time, to find another accounting office. In my job interviews, often when I was asked about a weakness, or asked if I had any questions, I would mention offhand, “I don’t really know what to do with negative capital.” So I discussed it with many interviewers, and got many one-sentence answers, from “you recognize capital gain on the partner’s schedule D,” to “these start-ups can have tremendous amount of value,” to, more commonly, a disappointed frown indicating this is not the sort of question that is appropriate to ask in a job interview.

In preparing for this paper I went back to my old office and asked the owner if she would be able to dig up the client’s operating agreement and vesting schedule for me to look at again. I told her I was writing a paper and wanted to see what was so baffling at the time.

She graciously gave me with the two items I asked for – the operating agreement (with its exhibit A) and the excel vesting schedule.

One of the pieces to the puzzle that drove me crazy during my research for this paper was – why would the developers have agreed to work for their partnership interests without any concept of the value? “I know how these freshly graduated MBA types peddle their wares,” I kept thinking to myself, “it doesn’t make sense.” I knew the gig. I myself had once worked in a startup (many lifetimes ago in my youth) and the founders were straight out of their MBA program, telling us how they spent two years in business school developing the idea for this company as a school project. So this client, where was it – the school had to have made them make a business plan, I know they must’ve had a virtual bill of sale when they convinced those developers to work for them. What is value but what marketing convinces you it is when you buy it?

In the course of the research to this paper, I returned to the vesting schedule, staring at a spreadsheet I had created two and a half years ago, where I had created scenarios (what would happen if there was a 50,000 loss in Year 2? 50,000 positive income in Year 2?).

The vesting schedule workbook had a couple other worksheets that I had never fully looked at before. In addition to the most recent vesting schedule, “Amendment 3,” there was also “Amendment 2,” “Amendment 1,” and “OG” (don’t know what the abbreviation “OG” was for, but it looked like the earliest draft of the vesting agreement). I studied the “Amendment 3” worksheet that we had used to report the ownership interest percentages on the return. I then idly flipped to the “Amendment 2” worksheet. And then to the “Amendment 1” worksheet. Each amendment looked basically the same as the prior, with the exception of some names and percentages. But there, on “Amendment 1,” a tiny cell at the bottom of one of the columns caught my eye, with a label beside it. “Valuation on 9/7/15:” and next to it: “$88,425.”

In the middle of confusion, by definition, nothing makes sense, but by taking a step back and looking with fresh eyes and going through the rules and concepts involved, and knowing what to search for, it begins to make some sense. Out of curiosity, two days ago I checked the Secretary of State website. The business dissolution papers for the company were filed only seven months ago.

[1] Reg. §1.704-1(b)(2)(ii) discusses consequences of a deficit balance in any one partner’s capital account, in terms of liquidation and obligations to creditors, the concept of deficit capital for a partnership as a whole can be inferred from this.

[2] Rev. Proc. 93-27, 1993-2 C.B. 343; Reg. §1.704-1(e)(1)(v)

[3] I.R.C. §61; I.R.C. §83(a); Reg. §1.721-1(b)(1)

[4] Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221; Prop. Reg. §1.83-3(l)

[5] REG-105346-03 70 Fed. Reg. 29675 (5/24/05); Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221

[6] McDougal, 62 TC 720 (1974)

[7] Treas. Reg. §1.83-1(a) (2003)

[8] Treas. Reg. §1.83-6(a) (2003)

[9] Treas. Reg. §1.83-6(b) (2003)

[10] Treas. Reg. §1.721-1 (2011)

[11] I.R.C. 752(b)

[12] I.R.C. §731(a)

[13] I.R.C. §83(a)

[14] I.R.C. §83(h)

[15] I.R.C. §108(a)

[16] Treas. Reg. §1.704-1(b)(5) Example (14)(iv)

[17] Treas. Reg §1.752-1 (f)

[18] Reg. §1.704-1(b)(2)(iv)

[19] “Infinite Series and Power Series.” Calculus with Maple Labs: (Early Transcendentals), by Wieslaw Krawcewicz and Bindhyachal Rai, Alpha Science International, 2003, pp. 541–542, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=16MjPAH_CBYC

[20] I.R.C. §705(a)

[21] REG-105346-03 (2005)

[22] I.R.C. §707(a)(1)

[23] Rev. Rul. 69-184, 1969-1 C.B. 256; T.D. 9766

[24] 81 Fed. Reg. 26693 (5/3/16)

[25] I.R.C §263; I.R.C. §83(h)

[26] I.R.C. §267(a)(2) & (e)

[27] I.R.C. §61; I.R.C. §83(a); Reg. §1.721-1(b)(1)

[28] Prop. Reg. §1.707-2

[29] Hensel Phelps Const. Co. V. United States, 413 F.2d 701 (1969)

[30] Rev. Proc. 93-27

[31] Rev. Proc. 2001-43, (8/2/2001)

[32] I.R.C. §83(b)

[33] I.R.C. §706(d); Reg. §1.706-4

[34] REG-105346-03 70 Fed. Reg. 29675 (5/24/05); Notice 2005-43, 2005-1 C.B. 1221

[35] “The Accounting Tradition.” Theory of the Measurement of Enterprise Income, by Robert R. Sterling, Scholars Book Co., 1979.

[36] Reg. 1.704-3(a)(6)

[37] Reg. 1.704-3(a)(10)

[38] Prop. Reg §1.721-1(b)(1); REG-105346-03